Retrospective: Egypt’s Revolution

Is it possible for the mob to spontaneously start a revolution and succeed? History says so.

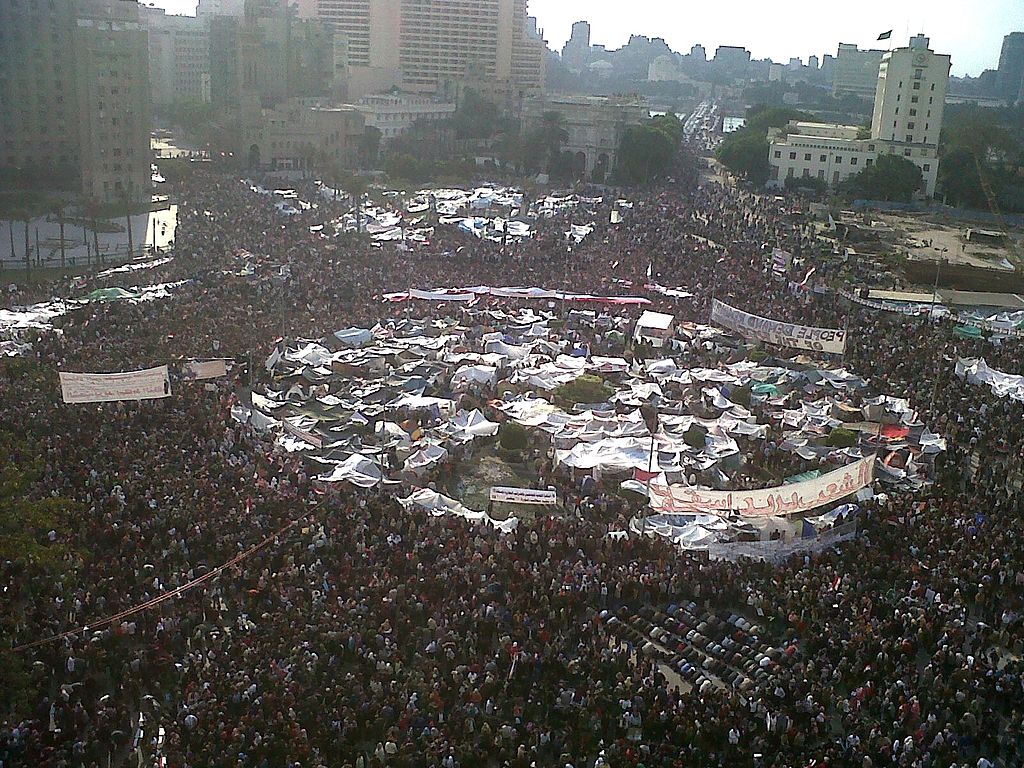

Tahrir Square during 8 February 2011. Mona, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Let’s go back eleven years, during the so-called Arab Spring, to revisit the Tahrir Square protest in Egypt that toppled Hosni Mubarak after decades in power.

It may have looked magical at the time; after all, it started with a merchant setting himself on fire in… Tunisia, and yet it started a revolution in Egypt. In this modern world we live in, calls for revolution can spread like wildfire worldwide in a matter of days and spur millions of people to demand change with their feet.

The revolution occurred not because the mob went mad over a video, but because it was meant to occur sooner or later. The drive for revolution usually isn’t collective insanity, but deep inequality and unresolved social issues. Egyptians wanted change because they felt they were left behind. The youth had no hope; if nothing else, there were no jobs. The government ruled by fear and authorities were utterly corrupt. And looking through the digital window, they wanted the freedoms and standards of living we’re enjoying.

So they spontaneously massed at Tahrir Square demanding that Mubarak step down, while the rest of the country was effectively on strike, just like that. And it worked, even though they had no strategy and no leadership. There’s a good reason for this: in Egypt, the military holds the balance of political power, and although it would rather not rule directly, like in Myanmar, it’s still asserting itself as a kingmaker. In the end, it’s the army withdrawing its support that did the trick. Although to get to that point, the mob first had to withstand police repression and hold its ground, which is key. The military effectively deposed Mubarak because he couldn’t maintain order, and it was easier to allow a transition of power than to shoot the mob.

Allow me to stress the above point: The mob succeeded because it stopped being afraid of the government. That is the most important point. One strongman can rule over a billion people if everybody is afraid of him (or his supporters by extension), but once the mob stops being afraid he’s just another dude wearing a suit. Strongmen know this, and that’s why they’re so eager to censor the web or block websites they can’t censor like Facebook.

That being said, there’s a flip side to this coin: They had no leadership and no strategy. And it came to bite them back in the most ironic fashion. When it became clear they had traded one tyrant for another, the protesters took to the streets again, this time to demand Morsi’s resignation barely a year after his inauguration. You read this right: the very people who revolted against Mubarak’s rule and elected Morsi revolted against Morsi, all but demanding military rule. This can only be seen as a failure of the revolution, and the reason is that there was no thought given to the follow-up. Without leaders, the mob left a power vacuum which was filled by religious fanatics who wanted to rule a previously secular society according to Sharia law, and by diktat at that. This is a crucial lesson to learn from this: Do not revolt only to leave a power vacuum. A successful revolution requires leadership, political involvement, vision, not just massive discontent.

So what to make of it? The Egyptian were eager for change, but not ready for it. And it’s not that they weren’t ready for freedom, but rather that they were not ready for self-determination. That’s why the country ultimately reverted to military rule; it wasn’t a coup but a counter-revolution by a people that hadn’t been giving much thought about what it would do with that freedom and how it would protect it.

Join Regime Change in BC on Facebook. And please read about civil disobedience before you do.

Discover more from Rulebreakers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.